Lesson Plan

Pancakes! (Grades 3-5)

Grade Level

Purpose

Students describe the physical properties of materials and observe physical and chemical changes as they examine the ingredients in pancakes and how maple syrup is harvested from trees. Grades 3-5

Estimated Time

Materials Needed

Activity 1: Pancakes, Pancakes!

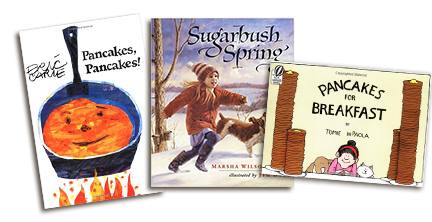

- Pancakes, Pancakes! by Eric Carle and/or Pancakes for Breakfast by Tomie dePaola

- Pancake ingredients (recipe may need to be adjusted for class size)

- 1 egg

- 1 1/4 cups buttermilk

- 2 tablespoons vegetable oil

- 1 1/4 cups flour

- 1 tablespoon sugar

- 1 teaspoon baking powder

- 1 teaspoon baking soda

- 1/2 teaspoon salt

1 gallon-sized Ziploc bag

1 gallon-sized Ziploc bag- Flat-topped electric griddle pan

- Measuring spoons and cups

- Pancake toppings such as syrup and butter

- Spray oil for the griddle

- Plates, napkins, forks for each student

- Butter-making Instructions (optional)

Activity 2: Syrup for Pancakes

- Sugarbush Spring by Marsha Wilson Chall

- Pancakes and Syrup activity sheet, 1 per student

Vocabulary

chemical change: a change that results in the formation of a new chemical substance through the making or breaking of bonds between atoms

physical change: a change in a substance that does not alter its chemical identity, including changes in shape, physical state, size, or temperature; this type of change is usually reversible

sapwood: the soft outer layers of recently formed wood between the heartwood and the bark

Did You Know?

- Maple syrup does not freeze.1

- Maple syrup is the only food that comes from a plant sap.1

- Only the color and flavor of maple syrup change according to the outside changing temperatures; this is known as a chemical change.1

- It takes 40 gallons of maple sap to make 1 gallon of maple syrup.1

- Maple syrup is only produced in the northeastern United States and eastern Canada, the region in which sugar maple is found.2

- Vermont produces the most maple syrup in the United States. They produce more than a half of a million gallons each year. Quebec, Canada is the largest producer of maple syrup in North America.2

Background Agricultural Connections

The little red hen of folk-tale fame planted wheat and worked hard to make bread. Wheat is at the center of many recipes; the hen could just as well have made pancakes! Pancakes are easily made in the classroom, allowing students to observe the changes that take place as ingredients become batter and batter turns to pancake. As students follow the recipe to make pancakes, they can observe the properties of ingredients at different stages—in their original form, after they have been measured and mixed, and after they have been cooked. This provides a simple and captivating introduction to the difference between physical and chemical changes.

Young students will not have enough experience to determine the difference between physical and chemical changes. Physical changes happen when the form, shape, or appearance of a material changes, but the substance of the material remains the same. Although it may be difficult, physical changes can generally be reversed. For example, mixing flour and sugar, tearing a large sheet of paper into smaller pieces, and freezing water are all examples of physical changes. In contrast, a chemical change creates a new substance with new properties that cannot be turned back into its original form. Cooking pancake batter and burning paper or wood are examples of chemical changes. Generally, a chemical change is irreversible and will create a new material that looks, feels, smells, and/or tastes very different.

The kitchen is a great place for students to make observations and explore the basics of chemistry. Almost all cooking has some basis in the physical sciences. Likewise, most cooking ingredients have some basis in the life sciences. Exploring food production helps engage students in the basics of biology. A discussion of maple syrup production also follows nicely after making pancakes.

Sugar maple trees grow in the northeastern United States; their natural range extends from Minnesota to Maine, south to Tennessee, and north into Canada. A stand of sugar maples that is managed to produce maple syrup may be called a sugar bush or sugar grove. Sugar maples with large, open crowns that gather lots of sunlight are best for syrup production. The sugary sap that is used to make maple syrup can only be harvested in the early spring and is the result of trees responding to seasonal changes in the environment.

During the summer, photosynthesis in the leaves of sugar maple trees turns energy from sunlight into sugar—the food that the tree needs to grow. Trees also need water to grow, which their roots take up from the soil. The trunk and branches are filled with vessels that circulate food and water throughout the body of the tree. In the fall, sugar maple trees prepare for winter by storing sugar and dropping their leaves. The trees go dormant and stop growing for the cold, short days of winter. In late winter, the trees sense that spring is coming. They begin mobilizing stored sugars, getting ready to grow new flowers and leaves. Normally, these sugars wouldn’t move through the tree’s vessels until the beginning of new growth, but the special combination of freezing nights and warm days forces flow in the sapwood.

On warm spring days following freezing cold nights, tapping into the sapwood of sugar maples yields buckets of sweet sap. Boiling and heating this sap condenses the sugars and causes a chemical change that produces the unique taste of maple syrup.

Engage

- Ask students what they ate for breakfast. As students name their breakfast foods, make a list on the board.

- Introduce one or both of the books Pancakes, Pancakes by Eric Carle and Pancakes for Breakfast by Tomie dePaola. Ask students if they can think of any reasons why cooking breakfast would be scientific. Prompt them to consider measuring, mixing, and heating ingredients to make something new. Some students may not have had any experience making pancake batter from scratch.

- Read one of these books to the class, stopping to ask what is happening in the pictures and what the next ingredient will be in the recipe. As you list each ingredient, ask the students if they know where it came from. Point out the source of each ingredient. Flour comes from wheat plants, eggs come from chickens, milk comes from cows, etc.

Explore and Explain

Activity 1: Pancakes, Pancakes!

- Tell the students that they are going to make pancakes by mixing ingredients together inside a Ziploc bag. Ask students to list the ingredients. Write the pancake ingredients list on the board, filling in the measurements and any ingredients that the students don’t mention.

- Ask students to observe and describe the ingredients before they are mixed.

- Have students make a storyboard or sequencing chart that allows them to describe each step that goes into making pancakes. Separating the steps will make it easier for students to recognize where physical and chemical changes take place.

- Ask the students:

- Have you ever made pancakes before?

- Did you make the pancakes the same way we are making them today?

- Did you use all the same ingredients in your pancakes?

- Where did the ingredients come from?

- When we measure the flour, are we changing the substance? Why?

- When we crack the eggs open, do the eggs change?

- What happens to the appearance of the flour when we add the buttermilk and eggs?

- What would happen if we didn't mix the ingredients together? Could we still make pancakes?

- Why will the batter look different after it is cooked? How should it look?

- Have you ever used a recipe before? Why are recipes important?

- Students should use observational skills and questions to think critically about the changes that are taking place.

- Have the students identify which steps of the process are physical and which are chemical changes (all of the actions are physical changes with the exception of the cooking of the pancake itself).

- Ask the students why following a recipe would be important in relation to what they know about physical and chemical changes.

- After the batter is ready, tell students that they are ready to cook the pancakes. Ask them to think about the batter and watch it very carefully as it is poured out onto the griddle.

- Ask the students:

What state of matter is the pancake batter? (liquid)

What state of matter is the pancake batter? (liquid)- How can you tell that it is a liquid? (it takes on the shape of the container)

- What would happen if we poured this liquid onto a cold griddle? (it would keep running until it reached the edge of the pan)

- Why does the heat make the liquid form a circle? (the batter begins to get solid as the heat starts to cook it)

- Explain to students that the pancake batter looks different, but it still contains the original ingredients. The batter changed from a liquid to a solid, and the substance is chemically changed because of the heat. It cannot be changed back into its original form.

- You may choose to make butter with the students (see Butter-Making Instructions) to highlight an example of physical change. Turning liquid cream into solid butter is a physical change because no new chemical substance is formed.

Activity 2: Syrup for Pancakes

- Read The Legend of Chief Woksis to the students.

- The Legend of Chief Woksis - "There is an Iroquois legend about how Native Americans in the northeastern part of North America discovered the sweet sap of the maple tree. This legend tells how the wife of Chief Woksis discovered maple syrup quite by accident while preparing venison (deer meat) during the Season of the Melting Snow. Woksis, the Indian Chief, went hunting one day early in the spring. He yanked his tomahawk from the tree where he had hurled it the night before and went off for the day. The weather turned warm, and the gash in the maple tree dripped sap into a vessel that happened to stand close to the trunk. Toward evening, Woksis's wife needed water in which to boil their dinner. She saw the trough full of sap and thought that would save her a trip to get water. Besides, she was a careful woman and didn't like to waste anything. So she tasted the maple sap and found it good-a little sweet, but not bad. She used it as the cooking water to cook her venison. When Woksis came home from hunting, he smelled the unique maple aroma, and from far off he knew that something especially good was cooking. The water had boiled down to syrup, which sweetened their meal with maple. Woksis found the syrup sweet and delicious. Thereafter, maple syrup was produced and celebrated each spring after the long, cold winter."

- Next, read the book Sugarbush Spring about a girl and her grandfather who tap sugar maple trees and tell the story of making maple syrup.

- Discuss the following questions:

Where does maple syrup come from? (sugar maple trees)

Where does maple syrup come from? (sugar maple trees)- What do maple trees need to grow? (water, sunlight to make food)

- Do maple trees grow in the winter? (no, they lose their leaves and go dormant to survive the cold temperatures and short day length)

- When can maple syrup be harvested? (only in the early spring when the days are warm and the nights are cold; it is the process of freezing at night and thawing out during the day that makes sugary sap flow in the sugar maple before spring growth begins)

- Discuss the purpose and function of a tree's trunk. In addition to supporting the tree's canopy, the trunk contains vessels that transport water and food, cells that produce new growth, and a protective covering of bark.

- Tell the students that they are going to act out the parts of a tree trunk by taking on the following roles and performing the following actions:

- The sapwood transports water to all parts of the tree. Have four students join hands to form a small circle around the central heartwood. Have these students chant, "We are sapwood. Gurgle, slurp. Transport water!"

- Phloem (flow-em) transports food from the leaves to the rest of the tree. Have six students portray phloem by forming a large circle around the sapwood. They should simulate phloem by reaching up above their heads to grab for food and then squatting down and opening their hands near the ground while chanting, "We are phloem. Food for the tree!"

- Ask five students to form a circle between the sapwood and the phloem to represent the cambium. The cambium layer produces new sapwood and phloem to keep the tree growing and healthy. Have these students join hands and sway from side to side while chanting, "We are cambium. New phloem and sapwood from cambium."

- The final component is the bark. Have eight students stand around the outside of the circle. Ask them to lock arms and be tough. The bark will protect the tree, so have the students march in place and chant, "We are bark. Please keep out!"

- When the tree is completely assembled, have all students act out and chant their parts simultaneously. Tell the students that you are going to chop down the tree and let them fall to the ground to complete the activity.

- Hand out the Pancakes and Syrup activity sheet for students to fill out as a class. They may fill in the blanks as you read the following paragraph:

- Sap is sugar that is stored in the trunk of the tree during the year. Sap flow requires cold nights (below freezing) followed by warm days. When a hole is drilled into the sapwood, the sap flows out of the tree. It takes approximately 40 gallons of sap to produce one gallon of syrup. In the sugar house, the sap is heated on a stove. This causes the water in the sap to steam off, condensing the sap, and creating a sweet maple flavor and a dark color not present before heating. This is a chemical change.

- Have the students try pure maple syrup on their pancakes or at a tasting station.

Elaborate

-

Use the book, Project Seasons: Hands-On Activities for Discovering the Wonders of the World written by Deborah Parrella. It provides interdisciplinary, hands-on activities for teaching children about the natural world.

-

Read pages 117-130 from the book Little House in the Big Woods written by Laura Ingalls Wilder. It gives an excellent account of tapping trees for maple sugar in chapter seven, "The Sugar Snow."

-

Share the book The Tree Farmer written by Chuck Leavell and Nicholas Cravotta with the students and discuss the many other ways that trees are used by people. This tale is told by a tree farmer who describes the gifts of trees and our responsibility to care for them.

-

Give each student a tree cookie and a section of yarn. Tree cookies are cross sections cut from tree trimmings—a great demonstration of the inner parts of a tree trunk. They are available in bulk from Nature-Watch in packages of either 25 or 100. Have the students write their names on the cookies and make necklaces. Ask them to identify the annual rings and determine the parts of the trunk.

-

Watch a 5-minute segment of the America's Heartland episode Creating Maple Syrup to see maple trees in New England and observe the process of making maple syrup.

Evaluate

After conducting these activities, review and summarize the following key concepts:

- The food we eat is produced by farmers.

- Farmers grow wheat to make flour, raise chickens to lay eggs, and raise cows to produce milk.

- Maple syrup comes from trees.

- A physical change occurs when the form, shape, or appearance of a material changes.

- A chemical change occurs when a new substance is formed.

Acknowledgements

Portions of Activity 2 were adapted from Project Seasons: Hands-On Activities for Discovering the Wonders of the World.

Recommended Companion Resources

- At Grandpa's Sugar Bush

- Let's Make Butter

- Maple Syrup from the Sugarhouse

- Pancakes for Breakfast

- Pancakes to Parathas: Breakfast Around the World

- Pancakes, Pancakes!

- Sugar Snow

- Sugarbush Spring

- Sugaring

- The Cow in Patrick O'Shanahan's Kitchen

- The Little Red Hen

- The Little Red Hen (Makes a Pizza)

- The Sweetest Season

- Wheat Weaving: How to Make a Corn Dolly

Author

Organization

| We welcome your feedback! If you have a question about this lesson or would like to report a broken link, please send us an email. If you have used this lesson and are willing to share your experience, we will provide you with a coupon code for 10% off your next purchase at AgClassroomStore. |